Veronica Redding remembers having a little bit of free time on her hands while she was working at the Oklahoma Historical Society.

"I really enjoy researching the history of Oklahoma, the history of my people—just the history in general is just really exciting to me," Redding said while sitting in the library at the historical society’s headquarters in Oklahoma City.

Redding is Osage and is from what’s known as the Hominy District of her tribal nation. She grew up going to dances and spending time at the family's summer home on their original allotment in Hominy.

On a slow day at work, she started looking around on the website Find a Grave, a citizen-compiled database of gravesites where users can upload information about their relatives, contribute information and photos on existing posts and create family trees that can be especially valuable to researchers and history enthusiasts.

Redding was using it to trace her own genealogy at Hominy Indian Village Cemetery.

"I thought, 'you know, I'm going to go through and see if I can find an obituary for every single person buried here,' Redding remembers telling herself.

From there, her research led her to look at other cemeteries at Gray Horse and more in Hominy.

What she found was a trove of obituaries that led to questions about deaths that seemed to have never been investigated and suspicions about her own family members, including her great-great-grandfather Charles Big Elk and his son Charles Big Elk Jr.

"My great-great-grandfather, he was, I call it, murdered in 1914, I believe. And then his son Charles Big Elk, which I also believe was murdered in 1936 — he was ran over on the highway between Pawhuska and Hominy," Redding said.

She pulls out his obituary, which reads, "Charles Big Elk died at Bug Creek camp last Friday and was buried the same day. The deceased has a right to 20-30 more years of life, but it was stolen from him by the booze seller. There'll come a time some day when when a judge who cannot be fooled will ask those officials the cause of Charly Big Elks' death and no subterfuge will go."

Charles Big Elk was born in 1874, two years after the Osage made their final move to Indian Territory in 1872. He married Cora Lohah Big Elk Pitts and had six children. Big Elk also held headrights.

Redding is suspicious because of the swift timing of her great-great grandfather's funeral. She said it wasn't a custom to bury Osages on the same day — she thinks it's a sign of foul play. And, she's seen other obituaries where people died a sudden and unexplainable death.

"An Osage Indian Girl, 20 years old died Sunday at Pawhuska and was brought to Fairfax and the funeral services held at Grayhorse. About three weeks ago deceased in company with her brother Herbert Brokey and his wife went to Colorado Springs, Colorado and at that time was in apparently as good health as ever" read an obituary from July of 1914.

"Young Indian Woman Dead" read another obituary from November of 1921 who went on to list her as "wasting away" from a long and chronic illness.

"I don't know, just with the timeframe and what was going on, you just don't know," Redding said referring to the timeframe of the Osage Reign of Terror.

"You know, there's always going to be that suspicion of was it really an accident?"

When the movie Killers of the Flower Moon premieres on the big screen, viewers will get a glimpse into the system that led to the brutal killings of Osage citizens for their wealth and land. Lurking in the shadows of the blackjacks, rock-ribbed hills, streams and fields of prairie grass was a system set in motion when Osages left their reservation in Kansas and moved to Indian Territory that allowed for widespread corruption.

Redding, like many Osages, thinks the Reign of Terror didn't just start and stop with the killings of Mollie's sisters and mother and Henry Roan: whose murders are central to the book. They point to a system that allowed the killings to happen and a lack of care or concern that included politicians, judges, bankers, businessmen and lawyers. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, whose duty it was to protect Osage citizens from graft failed to do so during this period of time.

The Osage people come to Indian Territory

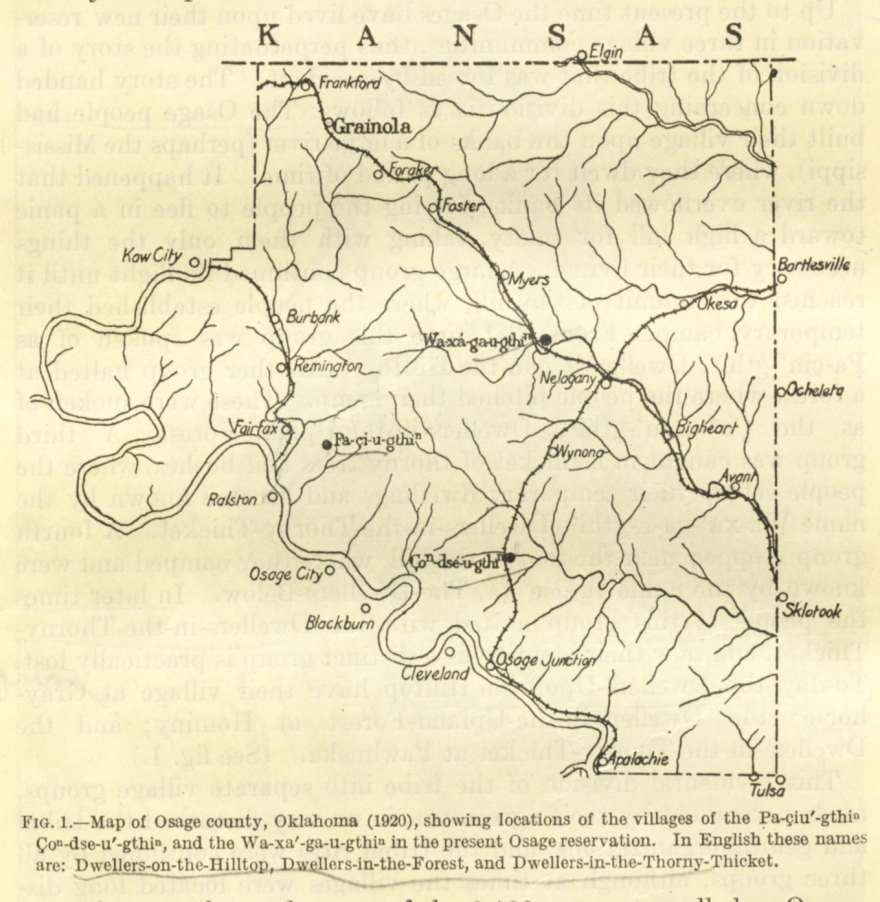

More than 150 years ago, the Osage moved from their reservation in Kansas and settled into an area about the size of Delaware. This was their final move after a series of treaties signed and promises broken from the US Government. Osages ceded most of Missouri, over half of Oklahoma and Arkansas and half of Kansas to the federal government through five treaties beginning in 1808.

Osages felt the brunt of westward expansion when land hungry settlers came to Kansas after the Civil War. In the 1870s in Kansas, non-Osages were illegally living on the Osage reservation and pressured Congress to move them off to make way for more people wanting land in the west.

Non-Osage people invaded Osage lands, killed the game they hunted, and stole their horses. A Bureau of Indian Affairs agent reported there are a "great number of people passing through their [Osage] country, since the establishment of Kansas Territory, in every direction, killing and destroying the buffalo and other game."

In one letter, A.A. Stewart, a person living illegally on the Osage reservation in Kansas wrote his congressman in 1870, "Mr. Clarke, hurry up the removal of these lazy, dirty vagabonds. It is folly to talk longer of a handful of wandering savages holding possession of a land so fair and rich as this. We want this land to make homes. Let us have it.”

Stewart may not be a recognizable name in the history books. But the Little House on the Prairie book series by Laura Ingalls Wilder is one. Wilder and her family were squatters on Osage lands.

The Osage removal to Oklahoma began with a treaty of 1869 as a result of all of the pressure placed on politicians. This treaty was negotiated between the Osage and the U.S. government and made way for their Kansas reservation to be sold to the government.

In 1872, the Osage bought their reservation from the Cherokee Nation from money from the sale of their Kansas reservation. The surplus of that money was supposed to be used for food, clothing and shelter as the Osages weren't allowed to leave their reservation to hunt buffalo. But, after failures from the federal government to produce these necessities, the Osage hunted anyway.

In Terry Wilson's book, The Underground Reservation: Osage Oil he describes the conditions Osages were dealing with when he quoted a commissioner on Indian Affairs.

"Commissioner J.D.C Atkins issued a special directive in February 1887 forbidding any Indian travel between reservations without prior consent of all agents for the tribes involved. Visiting, it seemed posed a threat to acculturation: possible depredations by traveling parties, absences from school and work, participation in dances and ceremonies and the exchange of strategies to oppose allotment," Wilson wrote.

Osages held the title to their new reservation in Oklahoma, and it gave them a considerable bargaining chip when it came time for allotment. Osages were already leasing their Indian Territory land to Kansas and Texas ranchers for grazing, and their government had laws that required cattlemen to acquire a lease from the Osage National Council. Leasing on Osage land already made Osages some of the richest people-even before oil was being produced and leases acquired.

In 1880, the Osage Nation formed a new government with a new constitution drafted by Chief James “Big Jim” Bigheart and his former schoolmate, attorney William Conner. Bigheart was educated at Osage Mission and served during the Civil War as a lieutenant in the Union Army.

In 1881, a new constitution was ratified among the Osages, making them a sovereign nation. But, their triumph was short lived — as allotment loomed and in 1900, the United States Government dissolved the Osage Nation's government.

Osages fought allotment after the Dawes Act was passed in 1887. They were among the last tribal nations in Oklahoma to accept it and one of their biggest conditions on accepting severalty: purge the Osage citizenship rolls of those who had no Osage ancestry.

Correspondence between the Department of the Interior and tribal leaders show the Osage Nation fighting to remove those who fraudulently claimed Osage ancestry. In1896, a letter listed people who claimed an ancestor that didn't exist or told of bribing tribal officials to get on the rolls.

In a letter dated August 1895, Chief Bigheart wrote to D.M. Browning, the commissioner on Indian Affairs. He sought access to the tribe's rolls before the 1880 enrollment cutoff date and for an investigation. The Osage Nation said there were 528 people whose names should be stricken who were illegally on the rolls.

"It perhaps may not be out of place for me at this time to warn the Department against many false and malicious reports sure to reach it on this subject, for I understand that the people whose rights are questioned are now at work getting up meetings, remonstrances etc and I feel that they will stop at nothing to prevent if they can, the proposed investigation," Chief Bigheart wrote. In the end, only 25 people were purged from the rolls.

Osage Refuse Allotment

In 1887, the Dawes Act, or general allotment act was passed. Also known as the Allotment Act, it was authored by Massachusetts Senator Henry Dawes and was intended to break up Indian communally owned land.

This was meant especially for Native people living in Indian Territory. The act parceled land off into 160 acres and then sold the rest to white settlers.

The 1887 Allotment Act did not apply to the Osage. The tribal nation’s National Council was required to approve allotment of the reservation. As a result, Black Dog and James Big Heart met with members of the commission and gave them several reasons why they opposed the act. Osages had not been paid yet for their Kansas land, there were many non-Osages on the tribal rolls and they didn’t want it. In an exchange, Strike Axe, a full-blood Osage, told the commission what he thought of the plan to allot Osages.

"When our chiefs sold reservations in the states the government would say, you were all hemmed in by whites and your Great Father does not want you to be bothered, just come down to the red man's country where you will not be disturbed. The government promised me when we came here that we would be the fartherest (sic) possible to be bothered and now you seem to think we are in bad shape with the whites. As you say, we have more whites than Indians but where shall we go?"

A New York Time Article from 1895 bore the headline: “OSAGE INDIANS REFUSED: They Reject an Allotment and Also Citizenship”.

The article explains how the Dawes Commission faced, "yet another setback" due to, "the commission having failed in its efforts to secure any kind of an agreement looking to the dissolution of the present form of tribal government, it was determined to secure a hearing before the young men of the tribe. The old full bloods were willing that the lands should be allotted, but it must all be distributed equally among the members so that there would be nothing left on which the white man could settle."

The Osage Nation held out against allotment. Under Principal Chief James Bigheart, the Osages retained ownership of the sub-surface, or mineral rights of their reservation.

Oil’s role in Osage Nation’s history

Oil was already being produced on the Osage Nation's reservation when the tribal nation finally agreed to allotment with the passage of the Osage Nation Allotment Act in 1906.

As early as 1896, Henry Foster, an oil tycoon from the east, was granted an exclusive lease by the Bureau of Indian Affairs "to explore for and extract oil and natural gas on the Osage reservation"

Even though the surface land could be owned by non-Osages, what was underneath, the oil was owned by the Osage Nation and placed in a trust managed by the federal government. Each person on a roll of Osages at the time received a share, which came to be called a headright. Every three months, each person who had a headright received a portion of the money from oil and gas drilling in Osage County. In 1907, upon statehood there were 2,229 Osage original allottees.

Headrights are a lot more than just oil money. Until the constitutional reform, the federal government didn't even consider someone a citizen of the Osage Nation unless they had a headright or a fraction of one. They couldn’t vote in Osage elections without them.

When oil production exploded, those headrights became incredibly valuable and outsiders, oil wildcatters and those wanting to make a quick buck flocked to Osage County. Osages became easy targets.

When the 1906 Osage Allotment Act was passed it was the federal government’s fiduciary duty to protect wealth and property of Osages.

But something happened when Oklahoma became a state, according to anthropologist Dan Swan. Swan was the first site director at the White Hair Memorial, which was once owned by Lillie Morrell Burkhart, an Osage woman who had more than two headrights.

Swan has written numerous books, including one about Osage weddings and another on the birth of the Native American Church.

"One of the conversations that took place at the federal level was the fact that so many Native Americans resided in Oklahoma and that the tribes and their citizens were subject to federal regulation, federal policy and federal law," Swan said. "The individuals working to gain statehood said that they readily accepted that, that they understood that Oklahoma was going to be a little bit different."

The Role of Guardians

The Oklahoma Enabling Act passed in 1906, a law that made way for Indian Territory to become a state. Tucked in the act was an important provision related to Native people. It said basically that nothing in the state's constitution would affect the federal government's authority with respect to Native people and their lands or disrespect the treaty rights.

Swan said that as soon as statehood happened, those who understood Oklahoma was going to be a little different immediately started working to undermine federal authority and federal policy in Oklahoma.

And in 1908 Congress passed a law that says that all probate actions for Native Americans in Oklahoma, particularly eastern Oklahoma, will be under the jurisdiction of county courts.

"As the erosion of their land base and territorial resources is slowly chipped away and forced to take individual allotments, they started to receive income from leases and in particular minerals and oil-the discovery of those resources on Native American reservations caused Congress to really take notice. And this is where the guardianship system comes in."

The guardianship system came with the passage of the 1906 act when many Osages were declared incompetent to manage their own affairs. Restrictions were loosened and tightened over the years-one of them was how much headright money congress should be distributed to those original allottees.

Swan said it became a system of patronage where county judges would appoint their friends as guardians. Osages received $1,000 per quarter, but that money would quickly get eaten up by guardians and lawyer fees.

"This wasn't something that you did out of the goodness of your heart to be a guardian, to educate Native American people about the workings of the American economy. This was about making a living by largely doing very little," Swan said.

In 1924, a congressional hearing was held over headright payments and guardianships. Bacon Rind, former Chief of the Osage complained to the commissioner about the guardianship system and the payment restrictions.

"I would like to dwell on the matter of guardianship," Bacon Rind said.

“Mr. Chairman and members of the committee, I appeared before you here many times on the matter of guardianship. We have told you what those people are doing and asking your aid, but I am at the point now, that I think the committee here is in sympathy with the guardians who have the affairs of the Indians in their hands," Bacon Rind was accusing the Department of the Interior of ignoring their concerns.

What the Osages want is to have a voice of their own, Bacon Rind told members of the commission. He said the fund restrictions were hurting elderly Osages-they need their money, he told members of the commission.

Another 1924 report published by the Office of Indian Rights Association titled "Oklahoma's Poor Rich Indians” excoriated the guardianship system.

“As the result of a careful, first-hand investigation of Indian conditions in Eastern Oklahoma by the undersigned, it is found the Interior Department all jurisdiction over Indian probate matters in Eastern Oklahoma and transferred it to the local county courts, the estates of the members of the Five Civilized Tribes are being, and have been, shamelessly and openly robbed in a scientific and ruthless manner. That all efforts by the Department of the Interior to have the County Courts follow rules of procedure that would afford a measure of protection to the Indians have failed. The rules promulgated by the State Supreme Court in 1914 were soon weakened, and then were annulled on July 10, 1923, by action of the Oklahoma State Supreme Court, leaving each County Court a law unto itself,” members of the commission wrote

It went on to detail the exploits of guardians explaining that, "the Interior Department is powerless under existing law to protect these helpless Indians from wholesale plundering because Congress vested exclusive jurisdiction over probate matters in the county courts in Oklahoma."

Newspaper articles from the 1920s show the commission's report playing out in full view of the public.

A 1923 article published in the Osage Journal told the story of a wealthy young Osage woman who said that a "second rate boxer" by the name of Wilbur "Bobby" Corbett drugged her, took her to Colorado Springs where she was forced to marry him and was regularly beaten by him.

"Uncle Sam steps in and Osage Nation attorney here to press sensational action; girl declares Bobby Corbett beat her and married her after administering drugs, kept her from communicating with relatives, charge," read the story.

The Osage Journal reported that the woman had 5,000 acres of "oil land" and that her income was $25,000 per year-adjusted for inflation that would be nearly a half a million dollars. Articles published after her death were led with sensational headlines including details about her "lavish spending" and abuse of alcohol.

In Trust, a podcast produced by Bloomberg and iHeart Media, told a similar story about an Osage woman named Rhoda Wheeler Ridge. She testified in an Oklahoma court that in 1924 she was forced to marry a man named Troy Pope. In court documents, she said he kept her from her mother Nah-me-tsa-he, even as she was dying and abused her and her children while signing and cashing her checks to get her money.

In Terry Wilson's book "The Underground Reservation" more than $8,000,000 were paid to 600 guardians in 1924.

Congress passed a law aiming to protect Osages from continued graft, but it wasn't adequate. There were complaints to county judges by the Osage Agency responsible for disbursing payments that many guardians were, "merchants who sold large bills of goods to their wards."

"In some cases, these accounts were so large that even if they were not barred by law they would be open to criticism on the ground that the guardian was not conserving his ward's estate,” Wilson wrote.

Simply put, the system was more profitable for the guardian than Osages, whom the system was set up to protect.

Another scheme involved men who would write letters to the Osage Indian Agency in Pawhuska offering to marry Osage women, presumably for their wealth.

One letter read, "I want a woman between the ages of 18-35 years of age, not a full blood, but prefer one as near white as possible…This is a plain business proposition and I trust you will consider it as such."

The letter is dated October 16, 1907 and comes from a man living in Joplin, Missouri.

"After Oklahoma became a state, there was an effort to sort of just wish away the reservations," Wilson Pipestem said. Pipestem is a respected attorney, a headright holder and was once counsel to the Osage Minerals Council-the body that oversees the mineral estate.

"Wish away the lands and protections that came from treaties and acts of Congress that directly benefit tribal nations and Native people," he said.

The Osage Reign of Terror as depicted in 'Killers of the Flower Moon'

William Hale was a rancher who arrived in Oklahoma from Texas in 1900. Hale was popular, a trick roper and a charmer that earned the nickname "King of the Osage Hills." He resisted attempts to move off the reservation by the Osage Agency Superintendent and invited members of his family to move from Texas to Oklahoma-including his nephew Ernest Burkhart, who married Mollie Kyle. Mollie and her sisters Anna Brown, Minnie Que and Rita Smith were original allottees and their mother Lizzie Q held three headrights.

Hale and Burkhart hired local badmen, like John Ramsey, to eliminate their victims. Anna Smith was found shot to death at the bottom of a canyon near Grayhorse. Her mother Lizzie Que died. Henry Roan, a full blood Osage man died after being shot in the back of the head. John Ramsey confessed to that murder saying that Hale had ordered it after he had taken out a life insurance policy on Roan.

And in May of 1923, Bill and Rita Smith's Fairfax home was blown up. The blast killed them alongside their maid Nettie Brookshire. Rita and Nettie were instantly killed but Bill lived for 10 days after that.

In 1926, Ernest Burkhart admitted to hiring the men to dynamite the Smith home. He also implicated his uncle William Hale and Ramsey in the death of Henry Roan.

On his deathbed Bill Smith was reported to have said that he had only two enemies in this world and that they were William Hale and Ernest Burkhart.

At the core of it was robbery efforts to steal resources and goods from Osage people, Pipestem said.

"These weren't crimes of passion, in my opinion-they weren't crimes of opportunity, as we use that phrase today,” he said. “These were calculated efforts that were driven by greed.”

It’s unknown exactly how many Osage died for their money, but Osage historian Louis Burns said, “I don’t know of a single Osage family that didn’t lose at least one family member because of head rights.”

The Osage Nation Today

Today, out of the 2,229 Osage headrights, nearly a quarter are out of Osage hands. The list includes the University of Oklahoma, various trusts, Catholic Churches, and a defunct care home called the Hissom Memorial Center, which was closed in the late 1994 after allegations of abuse surfaced. The Jack Drummond Trust bought half of headright from a man named OV Pope who acquired it from an Osage woman named Nah-me-tsa-he.

The Osage Nation is currently working with Oklahoma congressman Frank Lucas to pass a law making it easier to return headrights, but to date, nothing has hit the house floor for a vote in a politically divided Congress.

KOSU has reached out to the Bureau of Indian Affairs on this issue and did not immediately receive a response.

Veronica Redding's family still retains the title to her family's land 15 minutes outside of Hominy. The area is full of bois d'arc trees and green pastures. During the dances in June, family members come and stay at the summer house her great-grandmother Belle lived at with several cooks, maids and her children. Hanging on the walls are photos of her great-great grandfather Charles Big Elk and his family. On one shelf rests a well worn fishing pole belonging to her grandfather, Bell Charles Haney.

On a recent hot fall afternoon, Redding and her mother Cate pulled out albums of photos that their great grandma Belle took with her small camera-photos of people in front of the house that Veronica’s mom still owns, horses, animals and people having a great time.

Redding feels lucky to have her family's land intact, but says there's still questions that swirl around her great-great-grandfather Charles Big Elk's death.

Especially after she read an article from the 1920's about his death that read, "maybe someone will investigate his death some day."

"I mean it was just heartbreaking for me," Redding said.

Tara Damron, who runs the White Hair Memorial says the system that protected non-Osages needs more scrutiny and that the United State government should be held accountable.

"There's just so much corruption that was never investigated, that continues to be overlooked," Damron said.

Damron and her family are currently involved in a lawsuit over mismanagement of shareholder payments. In 2011, a similar lawsuit was settled when it was found that the federal government wasn't paying the highest posted price to shareholders. That lawsuit was settled for nearly $400 million.

"It continues to be protected by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and by the United States government to this day-to this day, 2023, not 1923, 2023," Damron said referring to how the Bureau of Indian Affairs has still not fully accounted for their releasing the full information about non-Osage headright holders.

For a long time, Osages didn't talk about this history, but with the movie Killers of the Flower Moon coming out, based on David Grann's bestselling book, more people are starting to.

"Now I don't have to carry those stories alone. We all can talk about it," one woman told KOSU after she had seen the movie at a screening for Osages last summer.

Today, Osages lay claim to some of the most accomplished people, Maria and Marjorie Tall Chief, George Tinker and Esther Quinton Cheshewalla, the first Indian woman in the nation to join the U.S. Marine Corps, Oklahoma City Mayor David Holt.

In 2004, the Osage Reform Act was passed that allowed the Osage Nation to determine who is a citizen of the tribal nation. Former Principal Chief Jim Gray, who was elected in 2002 ran on government reform. When the Osage Allotment Act was passed in 1906, it said that only those who had headrights or shares in the mineral estate could vote, meaning that a lot of Osages couldn't participate in their own government, couldn't vote.

The 2004 bill had two key lines: “Congress hereby reaffirms the inherent sovereign right of the Osage Tribe to determine its own membership, provided that the rights of any person to Osage Mineral Estate shares are not diminished thereby."

And….

“Congress hereby reaffirms the inherent sovereign right of the Osage Tribe to determine its own form of government.

In 2006, when the constitution became official Gray recalled those who formed the tribal government in 1880.

"And it was through that period of time that we reached within ourselves to find a new definition of Osage and it took leaders at the time, like Chief Bigheart, who had initiated and led an effort to draft a constitution of the Osage Nation,” Gray said.

A year after the new constitution was signed and implemented, he asked Osages what they wanted from their government. The thing he kept hearing was land-specifically buying the land back.

So, In 2016, the Osage Nation purchased Ted Turner's ranch: 43,000 acres for $74 million to be places in a trust. And, they've bought more property in downtown Pawhuska. They've built health care centers, a new meat processing plant and land to grow food in an aquaponics facility.

They're also working to get headrights back.

Today, the Osage Nation is urging congress to pass a law that will make it easier to transfer headrights back to Osages. Out of 2,229 headrights, the Bureau of Indian Affairs estimates there are around a quarter owned by non-Osage.

In 2011, the Osage Nation won a historic $380 million settlement when it accused the BIA of failing to pay the highest posted price to shareholders for oil leases on the minerals estate.

Like other tribal nations who successfully used the McGirt v. Oklahoma opinion, the Osage Nation is trying to get questions answered over whether or not their reservation was disestablished. Last year, a ruling in a case involving a man named Dustin Phillips delivered a setback, saying that it had been. But the tribal nation is preparing an appeal.

"McGirt is a case, in my mind, of one of great hope. But also great pain," Wilson Pipestem told the podcast In Trust.

Wilson said one of the biggest things McGirt highlighted to him was what could have happened during the 1920s — if the Osage Reservation had been recognized.

"That would have been federal jurisdiction over all of those murders, but they treated the Osage Reservation like it didn’t exist anymore. So you had to bring a case against somebody in Osage County Court where justice was not to be found, right. So it wasn’t until somebody was murdered on trust land — Henry Roan was murdered on trust land — that they decided it’s federal jurisdiction now," Pipestem said on the podcast.

The Osage people today can proudly say that at no point did they ever stop fighting for their land and for their sovereignty.

That's one thing Redding thinks about when she comes out to her family's land outside of Hominy, where her ancestors are buried, where they visit and stay during the annual In-Lon-Schka.

One headright that is outside of Osage control is the White Hair Memorial, the former home of Mrs. Lillie Morrell Burkhart. It sits between Fairfax and Hominy and was left to the Oklahoma Historical Society to be kept as a shrine to Chief White Hair, Lillie's ancestor. It's a research center now for Osages where language classes were held.

In September of this year, OHS announced that they would like to return control of the White Hair back to the Osage Nation-which was met with mixed reactions.

Tara Damron, the site director of White Hair Memorial hopes that with the movie coming out, more attention will be paid to the site and to getting headrights back to Osages.

"These are real people and we are still living with the trauma of that," Damron said referring to what happened in the movie

"Not only the loss of our people, but the loss of our land and the loss of our headrights and the system that is still in place. So, we're still fighting the system."