In a classroom full of future teachers at Oklahoma State University, Robin Fuxa instructs her students to count sounds in words like “map” and “can,” by placing pennies on a corresponding chart.

“Let’s look at ‘stop’,” Fuxa prompts.

“Ss-tuh-ah-puh,” her students respond in unison. “Four,” they count and move four pennies into the sound boxes on the chart.

Fuxa continues to demonstrate to her education majors different approaches for teaching literacy to their future students. They isolate sounds to see which ones are voiced — like “ah” — and which are unvoiced — like “k.”

They use tablet programs to record close-ups of their mouths as they form words. They cut out little boxes of word parts like “ch” and “ad” and “d” to create new words like “dad” and “Chad.”

The heavy focus on phonics is a major part of what’s called the “science of reading.” While there’s no single definition for the science of reading, it’s a generally accepted term covering a convergence of evidence on what works in literacy instruction — and that evidence says five methods are especially effective: phonological awareness, phonics and word recognition, fluency, vocabulary and oral language comprehension, and text comprehension.

The science of reading has been around for decades in some form or another, but a shift in what were thought to be best practices championed other methods that haven’t been nearly as effective. And now, fueled in part by a popular American Public Media documentary podcast on the subject, the science of reading is returning to the limelight, and Oklahoma schools and universities are using those techniques to teach literacy to the next generation.

With stakes higher than ever, Tulsa goes all-in on the science of reading

No district in the state has such a magnifying glass on its recent literacy rates as Tulsa Public Schools — whose accreditation status is on the line at every State Board of Education meeting.

State Superintendent Ryan Walters has targeted TPS in recent months, demanding accelerated improvement and condemning district leadership — ultimately culminating in the resignation of the district’s superintendent, Deborah Gist.

At an August Board of Education meeting, Walters warned TPS not to “test” him, saying that “every option” was still on the table — including a potential downgrade in its accreditation status or even a state takeover.

Then-board member Suzanne Reynolds reiterated Walters’ demands to TPS officials, telling them, “We can teach a child to read in a matter of a few weeks.”

Among the issues Walters cited in his case against TPS was the district’s low reading rates. 12.9% of TPS students meet or exceed grade-level standards for English proficiency, but the state average is 27.2%. To address that, the board demanded a plan for specifically teaching the science of reading to improve literacy rates.

Since then, the board has heard monthly updates from TPS officials. At the October meeting, TPS interim Superintendent Ebony Johnson outlined how the district is focusing on science of reading approaches to meet students’ literacy goals.

According to Johnson, 82% of TPS elementary teachers have been trained in the science of reading. By March 2024, she said the district is committed to training 95% of elementary and secondary teachers.

Johnson said the “aggressive” plan to tackle the district’s low literacy rates includes: intensive professional development and monitoring for teachers of science of reading techniques, requiring high-quality resources aligned to Oklahoma academic standards and monitoring for effective implementation, and using student achievement data to inform reading interventions and track student progress.

According to the district’s data projections, TPS is on track to have 700 more students proficient in reading by the end of the year, but their target is higher. Walters wanted more.

“We want bigger, right? We want much more than that, and again, I appreciate you saying that, as you always have,” Walters said at the meeting. “So what happens then when you look at that number and say, alright, well, we want, you know, 4,000 to be there, or whatever the number may be. How do we move that number to be a much more aggressive amount of students that are reading?”

At the end of the district’s presentation, Walters reiterated his threat that there was “nothing off-limits” for what he would do to make sure Tulsa Public Schools was successful.

Over the last seven and a half years, the district has transitioned to science of reading curricula. And in 2020, TPS began comprehensive training of its teachers in the science of reading.

Since 2020, more than 40% of its economically disadvantaged elementary students and nearly 47% of middle school students have met literacy growth goals.

According to Kelly Kane, executive director of early childhood education at TPS, 72 languages are represented in the district, and more than 34% of enrolled students are multilingual learners. With such a diverse array of learners, Kane says the district has gone all-in on the science of reading to meet those children’s unique needs.

“For all of our students at TPS, the science of reading is the key to helping our students master foundational literacy skills, which in turn can change life outcomes for students,” Kane said. “When more of our students have strong foundations of literacy, more of our students can then engage with grade-level learning, which ultimately sets them up for success not only in school but ultimately for college and for career.”

According to TPS, students receive on average 2.5 hours of daily reading instruction with a “state-approved, evidence-based curriculum.”

As TPS continues to develop its teachers in the science of reading, university teacher training programs are also focusing on the wide array of skills that learners need to be successful readers — though some say the training doesn’t go far enough.

A ‘constellation of skills’ needed to get kids reading

OSU’s Robin Fuxa said the phonics exercises are just one of many methods her students learn to teach literacy. She emphasized the necessity of using targeted assessments that individualize what kinds of instruction children need and adapting to those needs.

“There’s a constellation of skills that learners use,” Fuxa said. “So they’re going to be building back on their phonological awareness if they’re struggling to hear and identify individual sounds. Bridging that into phonics, when we get into written words and letters, letters and patterns. But then you’re also going to work on fluency and make sure they’re reading fluently.”

Comprehension, Fuxa said, is also not something that should be held off until other skills are mastered. Students should be writing as well as reading. And all of those skills are better fostered in an environment that is motivational and supportive. She said phonics is a critical part of the puzzle, but there’s more to it than that.

“That systematic phonics piece isn’t new,” Fuxa said. “How we conceptualize it [is], and certainly we’ve improved in how we teach it because we have increased our focus on the need for students’ background knowledge and building that up.”

Even though programs like the one at Oklahoma State University use science of reading techniques to teach literacy instruction, some groups say it’s not enough and the programs should go further.

Nationally, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality, only 28% of teacher preparation programs fully address all five components of the science of reading. And according to the NCTQ, none of those programs that cover all five components exist in Oklahoma.

Students “Walk to Read” every morning at John Burroughs Elementary

At Tulsa elementary schools, students spend each morning participating in “Walk to Read,” a dedicated time when they can interact with digital reading programs and receive targeted instruction in small groups with similar reading levels.

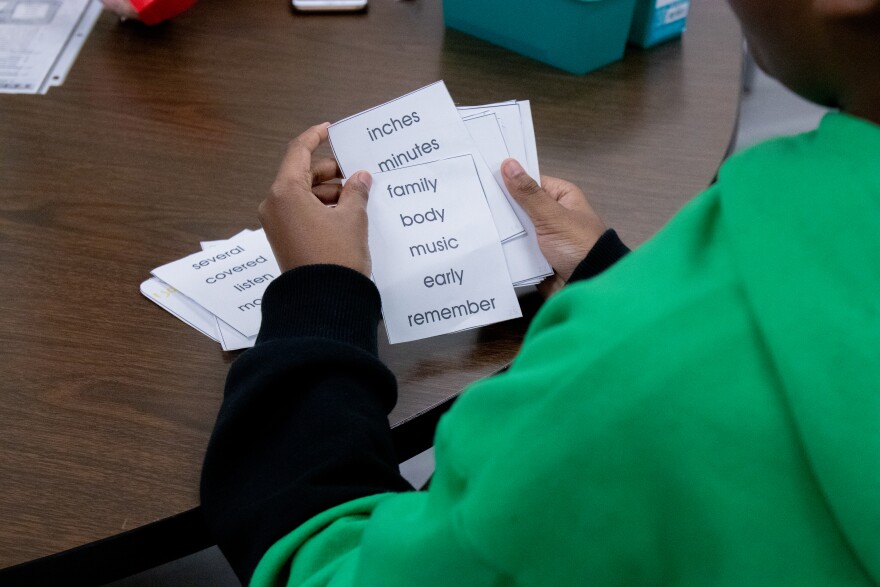

In Vicky Caldwell’s second grade classroom at TPS’ John Burroughs Elementary School, several students sit at a table with her while the rest work independently on digital programs on their laptops. The students at the table matched cut-outs of pictures based on the words’ beginning sounds.

A student lines up “bike” and “bus” next to a column with “shark” and “shoe.” When they finish their columns, Caldwell directs them to glue the pictures onto brightly colored paper. Tomorrow morning, another small group of students on similar levels will get to work with Caldwell.

Around the classroom, students with headsets read sentences and identify parts of speech on digital learning platforms. Some students are advanced — for instance, one second grader was reading a sentence about the Swedish parliament — and others are still practicing more foundational skills like sounding out one-syllable words.

The digital programs include Imagine Learning for multilingual students and the AI tutoring program Amira for other students.

Before using it district-wide, TPS began using Amira last year to support students with dyslexia. It gives students benchmark assessments to tailor lessons to a specific child’s current ability level, it provides real-time corrections when students make mistakes, and it tracks their progress through data.

In studies from several universities, Amira was about as effective as a certified human tutor. And a study from Columbia University found that a year of instruction from Amira nearly doubled the effect size on literacy development compared to just human tutoring alone.

But like most technology, the program isn’t perfect, and there are still some kinks to work out.

For instance, during a Walk to Read time on Tuesday, some students at Burroughs Elementary experienced difficulty in getting the program to recognize their voice amid a cacophony of their peers speaking into their own laptops. Some students appeared slightly frustrated, trying to prompt Amira repeatedly with the program’s trigger phrase, “I am ready to start.”

But Kane said the district is constantly assessing where those “gaps” are that need to be filled and finding ways to address them. Outside of the digital learning platforms, teachers engage in collaborative, frequent and ongoing teacher training and planning for maximizing science of reading approaches. Additionally, she said many TPS schools are leveraging federal funds to hire dedicated reading interventionists.

Despite experiencing declines in student achievement during the height of the pandemic, Kane said things are looking up for Tulsa students.

“We know the stakes are very high and we have an incredible sense of urgency. (...) And we are starting to see those gains. Not as fast as we need to — we know that we need to really accelerate growth for our children in order to have the number of students proficient that we need,” Kane said. “But we think we’re moving in the right direction with the work that we’re putting in place.”