In 2003, now-Cleveland County District Judge Michael Tupper began his career as a prosecutor. As a “young, fired-up crime-fighter,” Tupper said the perception of drug and alcohol treatment courts had a connotation of being “soft on crime.” But during his time as a prosecutor, his understanding of treatment court began to shift dramatically.

“I was ready to go after the cartels and the drug pushers and the bad people. And as time went by and case after case was coming across my desk, I realized that I wasn’t seeing these bad people,” Tupper said. “I wasn’t seeing the cartels and the drug kingpins. I was seeing everyday people that are struggling.”

Tupper said once he learned about the neuroscience of addiction and saw how easily people got entrenched in the cycles of the criminal justice system, it changed him.

“I’ve had a front-row seat for 20 years of seeing people recover from addiction,” Tupper said. “When I get to go to treatment court and work with people who are doing something about their issues, and we’re lifting people up and improving situations, yeah. It changes you. How could it not change you?”

Treatment court: How it works

Tupper presides over the Cleveland County Treatment Court, a position he’s held since 2013. The court has been in place since 2000 and serves as an alternative to prison for people who commit non-violent felony drug- or alcohol-related offenses in Cleveland County.

According to the FY21 Oklahoma Criminal Justice Programs’ Manual, treatment courts must use a team of professionals that include: a treatment court judge; a district attorney representative or prosecutor; a defense representative; a coordinator who oversees program operations; a service provider who supplies therapy sessions, case management and monitoring; and a community supervision provider who monitors participants outside the court, including conducting home and job visits.

Treatment courts are structured in phases that become progressively difficult. Once a team has determined a participant has progressed toward their treatment goals, the participant can move to the next phase. In Cleveland County, a participant must pass five phases before being eligible for graduation. Tupper said it can take between 14 months to two years to complete the program.

In Tupper’s court, all participants must sign a performance contract. They get regular substance testing — a missed appointment or positive drug test could mean disciplinary actions anywhere from an ankle monitor to dismissal from the program — regular appointments with counselors and case managers, group therapy and self-improvement activities. On top of weekly mandatory court hearings to check progress, the program is demanding, and not everyone meets those demands.

“We usually have around 80% graduation rates, which is phenomenal,” Tupper said. “Not everyone gets there, unfortunately, and the ones who don’t, we go through every step we can to try and change that behavior. [If] it’s not changed, then they’ll get terminated.”

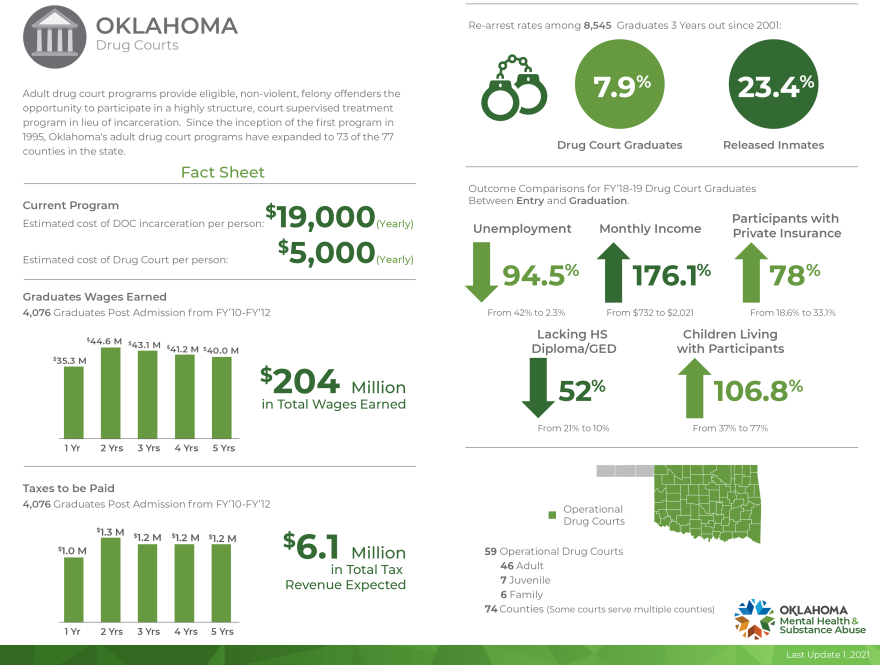

Statewide, drug treatment courts boast several impressive statistics. According to the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse — the entity overseeing the treatment court program — offenders released from prison are re-arrested at a rate about three times that of offenders who graduate from treatment court. Between entering treatment court and graduating, unemployment numbers for participants drop by nearly 95%. The percentage of children able to live with participants more than doubles and participants’ average monthly income increases by 176%.

Four recent bills have impacted drug offenses: State Question 780, which changed the classification of simple drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor and went into effect in July 2017; SB 649, which reduces enhanced sentences for certain repeat nonviolent felonies and went into effect in November 2018; SB 793, which removed life without parole as a sentencing option for convicted drug traffickers and lowered possible sentences for possession of certain drugs, and also went into effect that November; and SQ 788, which legalized medical cannabis and went into effect with the debut of the Oklahoma Medical Marijuana Authority online application process in August 2018.

Recent analysis from the Oklahoma Policy Institute revealed a sharp drop in the number of felony drug offenses and a substantial increase in misdemeanor drug offenses. One year after SQ 780 had taken effect, felonies for drug possession fell by 74.4%. Inversely, drug possession misdemeanors climbed by 166.3%.

Jari Askins, the state administrative director of courts and former lieutenant governor, was a state representative in 1997 when she co-authored legislation to allow the state to tap federal matching funds for drug treatment court. The move expanded the reach and resources of the few existing treatment courts across the state, as well as added dozens of treatment courts in more counties.

Askins said while SQ 780 decreased Oklahoma’s projected prison population as intended, one unintentional consequence was taking people out of consideration for drug treatment court. Because simple drug possession is now classified as a misdemeanor instead of a felony, and treatment court is for drug felonies, fewer people may get the opportunity for treatment.

The felony charge and accompanying prison sentence, Askins said, provided an incentive to choose drug court as an option, but the maximum punishment for a simple drug possession misdemeanor in Oklahoma is one-year imprisonment and a fine of $1,000. Even if Oklahoma had a misdemeanor treatment court system, taking the treatment court option would be a hard sell.

“[A felony charge] was the catalyst for people choosing to participate in and give drug court a try — rather as a diversion from prison,” Askins said. “[When SQ 780 went into effect], those judges that handled drug court were extremely worried about how their numbers would drop. Not because they were worried about numbers, but they knew that it meant there might not be the hammer to hold over people to encourage them to get this treatment.”

Even if Oklahoma used misdemeanor drug treatment courts, it may be difficult to persuade offenders to go through a demanding and lengthy program like treatment court if the alternative is something like community service or a fine. Askins said figuring out how to pivot after SQ 780 has been challenging because the change from felonies to misdemeanors has “really taken a shift in philosophy — a shift in understanding.”

As for arrests, by 2020, drug-related arrests dropped by 44% from where they had been in 2016, the year before the first of the three bills went into effect.

Askins said that drop might offer insight into how police departments are handling misdemeanor drug arrests.

“Many law enforcement officers, it takes them more time to do paperwork on a misdemeanor where nothing’s really going to happen,” Askins said. “And so, a lot of times, we are seeing a drop in the number of cases in that area.”

Another notable trend in Oklahoma’s crime reporting data was the jump in drug offenses during the pandemic. According to OSBI, which is updated monthly, drug violations and drug equipment violations spiked by 25% from 2020 to 2021 after remaining fairly steady for the preceding four years.

‘This was a chance’

Former Oklahoma lawmaker Cal Hobson, D-Lexington, used to push legislation aimed at reforming the state’s criminal justice system — including authoring two bills in the ’90s to expand drug courts. In 2014, he found himself in a treatment court after wrecking his car while driving under the influence in Cleveland County.

“It is just miserable to walk up [to the podium during drug court hearings]. Say your name. Say the number of days [of sobriety], look at the judge,” Hobson said. “You know, you used to fund the courthouse, fund the budget here. You’re now standing in front of those guys.”

Hobson said he’d been in every prison and most jails around the state when he used to be one of the lawmakers in charge of the corrections budget. Staying overnight in a jail cell, with “rubber shoes and a mattress and… nothing else,” sharing the cell with a man who “yelled and threatened” him all night long, gave Hobson a new perspective on Oklahoma’s criminal justice system. Staring down a potential prison sentence, he said, provided ample incentive to take treatment court — and his sobriety — seriously.

Hobson said the stress of being president pro tempore of the Senate had led to things getting “out of control” with his alcohol use. While he’d been to treatment centers before, sobriety never stuck. But since his time in the Cleveland County Treatment Court over seven years ago, Hobson has maintained his sobriety.

“I do not say that [treatment court]’s the reason I’ve been able to stay sober — I don’t know the reason. I just know I have,” Hobson said. “But drug court was a very important part of it. And Judge Tupper and others, because of the way they dealt with me so professionally, I knew that this was a chance I should not screw up.”

Hobson was close to some other participants during his time in the program — the “kids” as he calls them, given he was usually decades their senior. He’s stayed in touch with some, and he’s seen others die of drug overdoses. He said the work done in treatment court doesn’t stop at graduation. Sobriety for him still isn’t automatic — it’s a daily choice.

“I have a motto now that I routinely follow every day. When you get up in the morning, you really have only two choices for that day: you can either have a good day or a bad day. And ever since drug court, on almost every day, that’s how I start the day,” Hobson said. “I would love to go with some of my pals off to the Interurban [restaurant] and have some drinks at the bar and a steak and talk politics. [But if I do], I’m not going to end up having a good day. So it keeps me sober to stay on that path of having a good day, every day.”

A ‘no man’s land’: Criticisms of treatment court

While some see treatment courts as helpful, others see them as problematic. Askins and Hobson see both: a vital lifeline with a proven track record, but with glaring issues lawmakers have yet to remedy.

They point to the potential for a disparity of care in rural Oklahoma, where treatment courts may not have the same resources Oklahoma, Tulsa and Cleveland counties have. If you’re going to commit a crime, Hobson joked, do it in a county with a good treatment court.

Currently, 59 treatment courts serve 74 of Oklahoma’s 77 counties. There are no treatment courts in the three panhandle counties: Cimarron, Texas and Beaver. And not all treatment courts, Hobson said, are created equal.

“There’s just huge voids in Oklahoma,” Hobson said. “It’s no man’s land.”

Due to the customizable structure of Oklahoma’s treatment courts, much of the decision-making lies with two main actors: district attorneys and judges. District attorneys decide who gets to participate, and judges decide how lenient or strict to be during the program. While some judges may levy a relatively small penalty for a missed court hearing or failed drug test, judges have the authority to boot participants for failing to adhere to the program.

Aila Hoss, an attorney and professor at the University of Tulsa who specializes in health law, said drug treatment courts are a result of not having adequate, accessible healthcare for people with addiction disorders. Healthcare, Hoss argues, should not be predicated on being convicted of a drug felony.

“But what’s the alternative, right? Burn it all down, cut it down, substantially invest in our healthcare system. And that takes courage,” Hoss said. “It’s way easier to spend $20 million on some problem-solving courts than is to be like, ‘Oh, we actually have to think of a completely new model.’”

Another criticism of treatment courts is the use of fees. Hobson said participants must pay thousands of dollars in fees, including to have their urine tested. He said he was privileged to be able to afford the fees, but not everyone can.

“[Other participants] are not, by and large, college graduates, PhDs,” Hobson said. “These folks come up hard. … A lot of them stand up alone and go out that door back to pretty tough environments, or nothing — headed back to under that bridge.”

According to the criminal justice manual, “treatment services shall not be contingent on paying any required fee or copay.” Judges also have the discretion to waive fees for participants.

Hobson said getting the state to pay for court fees is a hard sell. When there are budget gaps at the capitol, increasing fees, fines and assessments on people dealing with drug and alcohol violations is “one of the easiest ways,” to fill them.

“It’s easy to sit there as a legislator, and the guy says, ‘Right now we charge $20 for a drug test, all we’re asking is to make it $22,’” Hobson said. “Because we have a million-dollar budget shortfall, so you say yes, because most of the public doesn’t see the extra $2.”

Hoss said the public sees the continued stigmatization of substance use disorder as a “moral failing.” People who use substances, she said, are looked at as “undeserving of a better system.”

“Investing in folks with substance use disorder is so offensive to so many people,” Hoss said. “If the goal is getting reelected or getting elected, it doesn’t make sense for a lot of policymakers.”

The stigmatization, Hoss said, also creates major obstacles for more progressive drug policy, such as medication-assisted treatment and monitored use at safe consumption sites. Askins said while she sees how medication assistance can be “extremely appropriate” for “very, very high risk, highly addicted” people, Oklahoma lacks resources to provide sufficient in-patient programs. The inability to address severe substance abuse disorder, Hoss said, is a problem.

“How do we create safe spaces for people who use drugs who may never make it to recovery, nor want to get to that point of recovery?” Hoss said. “[Are] there safe consumption sites, harm reduction strategies? And so this is where you get into the pushback of enabling the drug use.”

‘Show up, be honest and try’

Late in the morning on a Tuesday in December, Judge Tupper’s treatment court met for another regular session. He began the hearing with the standard announcements: a reminder of the weekly running group and an upcoming Christmas drive-thru luncheon. But that day’s proceedings featured something special — a participant was graduating from treatment court.

The graduate — who asked to remain anonymous because his conviction was removed from his record upon graduation — was asked the question Tupper begins all of these conversations with:

“What are your days of sobriety?”

The graduate answered he’d been sober for 411 days. As his final requirement for graduation, he then read his petition to graduate in front of the court. He said he’d pled into drug court in November of 2020 with a felony DUI and faced 5 years in the Department of Corrections if he failed the program.

“Drinking was a vicious cycle that kept me focused on self-centered behaviors with little regard for anything or anyone else,” the graduate read. “Sobriety has opened my eyes and caused me to cherish and value these things once taken for granted. … It’s important that I keep sobriety first in my life, because if I don’t have it, everything that’s dear to me can be lost. … With all that being said, I humbly ask to graduate from the Cleveland County Treatment Court program.”

After applause, Tupper’s official graduation announcement and receiving a card signed by his care team, the graduate was able to walk away with his 5-year prison sentence off the table and his continued journey through sobriety ahead of him. But before leaving, he gave some parting words for the participants sitting behind him:

“Show up, be honest and try,” the graduate said. “My advice to you is to please take this program and use it to stay sober and get in recovery. Because this is the time to do it.”