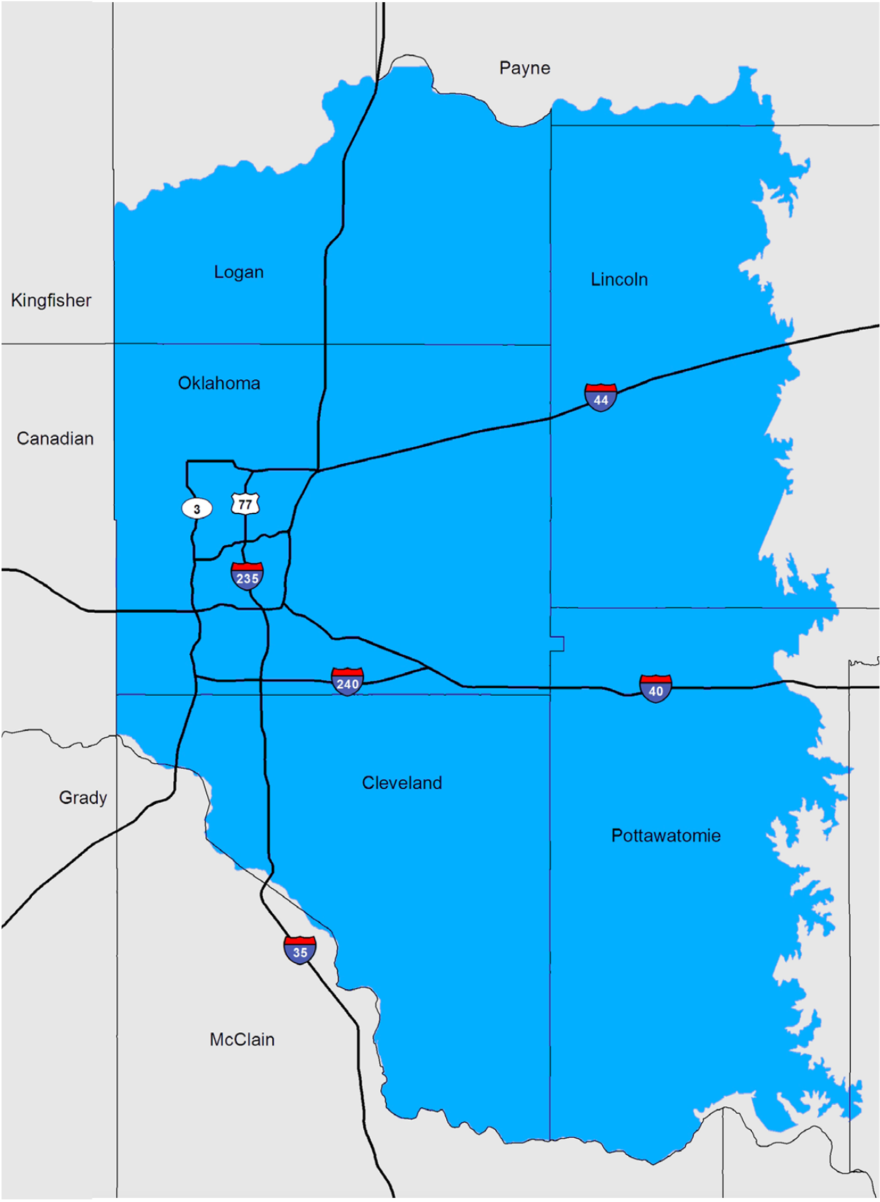

If you’re reading this in central Oklahoma, there’s a good chance you're above the Garber-Wellington Aquifer.

It’s an underground sandstone formation that acts kind of like a sponge, soaking up water from above and holding it. This sponge is a slab of sandstone hundreds of feet thick that spans over 3,000 square miles.

Shana Mashburn is a hydrologist who studies Oklahoma’s aquifers with the U.S. Geological Survey. She says the Garber-Wellington has shaped urban development in central Oklahoma for over a century.

“Back then it was steam engines, and they needed a lot of water,” Mashburn said. “So there were wells that were drilled into the Garber that supported those communities and those railroads, but eventually they turned into cities.”

Oklahoma City, Edmond, Norman — all those cities and more sit on the Garber-Wellington, and the area’s population is still growing today. But as the metro spreads east into farmland, some worry about the future of the aquifer. Among them is Frank Patterson, who lives in the Oakdale area of northeastern Oklahoma City.

“It's very important for us to understand putting high-density housing, what it does to the aquifer,” Patterson said at an Oklahoma City Planning Commission meeting earlier this year.

He was there because he’s concerned about a patch of forested farmland near his house. Local developer Ideal Homes wants to buy that land and build 655 houses on it, but they need the city to rezone it first.

“If we approve this 200-acre high-density development, there will be one,” Patterson said. “There'll be another one after that, there'll be another one after that in the same area, because there are thousands of undeveloped acres in this area.”

Maintaining well wellbeing

This proposed neighborhood would be denser than many of its neighboring communities — about 3.5 homes per acre on average. This development wouldn’t bring more wells to the area— it would be entirely on city water. But it’s on a particularly important spot for the aquifer. This area’s sandy soil and natural contours make it especially good at getting water into the earth to replenish the aquifer’s stores.

Rooftops, sidewalks and roads turn rainwater into runoff, which flows into storm drains or floodways rather than soaking into the ground. And the areas of Oklahoma County that are covered in these waterproof surfaces have grown by 20% since 2001..

Local resident Callie Stuckey says she worries that if the city doesn’t consider groundwater and runoff as it grows, people who rely directly on the aquifer will be in trouble. Stuckey’s family lives just east of the proposed development and uses a private well to pump from the Garber-Wellington.

“It may not happen in a year or two years, but eventually I think it will dry up,” Stuckey said. “And then my husband and I will be responsible for drilling another well on our property. And if that one isn't successful, we would have to pay out of our pockets to tie into city water.”

She said that could cost upwards of $100,000 because existing city lines are so far away.

Stuckey isn’t alone in her concerns — Patterson said there are nearly 450 residential wells within a mile and a half of the proposed development, and some of them are already having issues.

“We can't go much deeper because we run into saltwater,” he said. “So we're stuck. The neighborhoods to the east of here and to the northeast of here do not have city water available to them. So the aquifer is our only option.”

The Cross Timbers

In response to concerns about the density, Ideal Homes redrew the development plan with 30 fewer houses and more open space. But area resident Gypsy Hogan says that’s not enough.

“To argue over whether it's going to be 688 houses or 655 doesn't matter,” Hogan said. “They're going to clearcut. And that's the argument to me is: Can we not have development of some kind that doesn't clearcut and set a precedent for moving into the Cross Timbers?”

Hogan lives a few miles south of the development, in a stone house surrounded by trees, mostly post oaks and blackjacks. This whole area is part of the Cross Timbers — the border where the forests of the Eastern U.S. shift into the Great Plains. The region generally follows the boundaries of several sandstone aquifers, including the Garber-Wellington.

“The only reason the Cross Timbers are still here is because they weren't the great tall oaks that produced lumber,” Hogan said. “It’s just such a scrappy area.”

But chunks of the Cross Timbers are gone. Oklahoma County lost about 8% of its forestsbetween 2001 and 2019.

“The neighborhoods that are complaining about our rezoning were almost 100% forested,” said David Box, an attorney representing Ideal Homes before the Oklahoma City Planning Commission. “It wasn't but for a developer clearing the land that allowed for their homes to be built.”

Ideal Homes’s representatives said that removing trees could actually help with aquifer replenishment. Mashburn, the aquifer researcher, said that could be the case because their canopies soak up so much water before it reaches the ground.How development could impact a local school

There are going to be other benefits for local residents, Box told the planning commission. Oklahoma City commissioned a study on housing affordability in 2021, which found that the city needs more high-quality, affordable housing.

“That's exactly what we're doing here,” Box said. “We are providing the opportunity for teachers, firemen, police and emergency service workers to live in an area that has a great school district.”

But residents say they’re concerned the school district isn’t equipped to handle more people. There are only about 1,500 households in the Oakdale Public School District, so the proposed development could expand the student population dramatically.

Superintendent Carl Johnson says the school district will embrace as many students as it needs to.

“I want every family that walks through the door to feel welcome and to receive a quality Oakdale education,” Johnson said. “What I am concerned by is the idea that we’re involved in planning this — we are not.”

If the City Council approves this development, the school will need room and funds to grow. But Johnson says the practicalities of that growth are uncertain.

Ideal Homes has promised to give 5 acres of the land to the Oakdale School District and offered to sell the other 15 acres at cost. But Johnson says the developers couldn’t tell him what that cost might be.

“They might sell this plot to anyone,” Johnson said. “It may be out of reach for us.”

Mounting resistance

The residents of nearby neighborhoods have taken their concerns to city officials through emails, phone calls and private meetings.

“We just want them to hear us and really take to heart our concerns,” Stuckey said. “Because when you're talking about a community source of water, that is life-affecting. It’s life-giving.”

Stuckey’s is one of over 500 signatures on a petition against the rezoning, all from people who own land within 2 miles of the proposed development.

“I don't know that we've ever received the sheer volume of letters and phone calls from any neighborhood for any development in my five years on the commission,” said City Planning Commission chairperson Camal Pennington.

The Commission voted to recommend approval of the development earlier this year. The power to approve or deny the rezoning application lies with the City Council.

“I think it's a foregone conclusion that this site is going to be developed single family,” Box said at that Planning Commission meeting. “And we think… that this particular developer is the best suited to develop the site.”

Hogan says no matter what happens with the zoning decision, residents and developers should start paying more attention to the Cross Timbers and the Garber-Wellington Aquifer.

“If people don't know that these are the Cross Timbers, if they don't know that this tree could be 200 to 400 years old — then they don't know what they're cutting down, bulldozing, clear-cutting,” Hogan said. “But if they name it and go from there, then they can learn more about it.”

City Council is scheduled to consider the application on Tuesday, May 9.