Freedmen is another term for descendants of former slaves. And in the Five Civilized Tribes in Oklahoma, the question of their status within the tribes has been debated for decades. In the Cherokee Nation, there are two open court cases that will determine the freedmen’s tribal citizenship. And a similar debate is happening in the Seminole nation.

In this third and final story in our series about the Freedmen, Invisible Nations’ Allison Herrera explains why the Seminole freedmen feel especially angry about the actions of their tribal council members.

LeEtta Osborne Sampson sifts through a pile of yellowed, worn documents at a library in Midwest City. She’s showing me tribal identity cards and records containing information about her ancestors from the Dawes Rolls. Some cards belong to her dad, grandfather and other relatives. One record stands out.

“This is Minerva Moppins, who’s my great, great grandmother, who we all stem from. The reason I brought this is to show you how deep and how long we’ve been in this tribe.”

LeEtta’s ancestor Minerva Moppins was a Seminole Freedmen - one of about 2000 descendants of freed slaves who consider themselves part of the Seminole nation, by law. The law dates back to 1866. Like many in the south at that time, native tribal members owned slaves. When slavery was abolished, the US and all Five Civilized Tribes signed a treaty granting citizenship to those freed slaves. They would now be full members of the tribe. Fast forward 150 years, and the tribes are now debating the meaning of that treaty.

“In Seminole nation’s 1866 treaty, we have a paragraph and a half, that they wrote on us. ‘As long as the grass grows and the rivers flow, we shall be one,’” explained LeEtta.

Does it grant them full citizenship rights or not? Full citizenship includes access to housing, health care, job placement programs and other benefits. And tribal members now argue that the only people who can access those full rights, are those who can prove their ancestry by blood. LeEtta Osborne Sampson says changing rules after all this time is racist.

“We are members of this tribe and they still deny us because we are black. But we can date back as far as 1666 that we are Seminole.”

Jon Velie, the lawyer who represented LeEtta and other Seminole Freedmen in 2000 when the tribe tried unsuccessfully to kick them out, explained what happened before he took up their case.

“When the Seminole nation voted the Freedmen out of the tribe, the US said it would cut off it’s government to government relationship with the Seminoles, if in fact they had the election and then went through with voting them out. So, when the Seminoles did that, the United States did not recognize the Seminole nation. Cut off funding to them. Fined them $11 million dollars for gaming illegally,” said Velie.

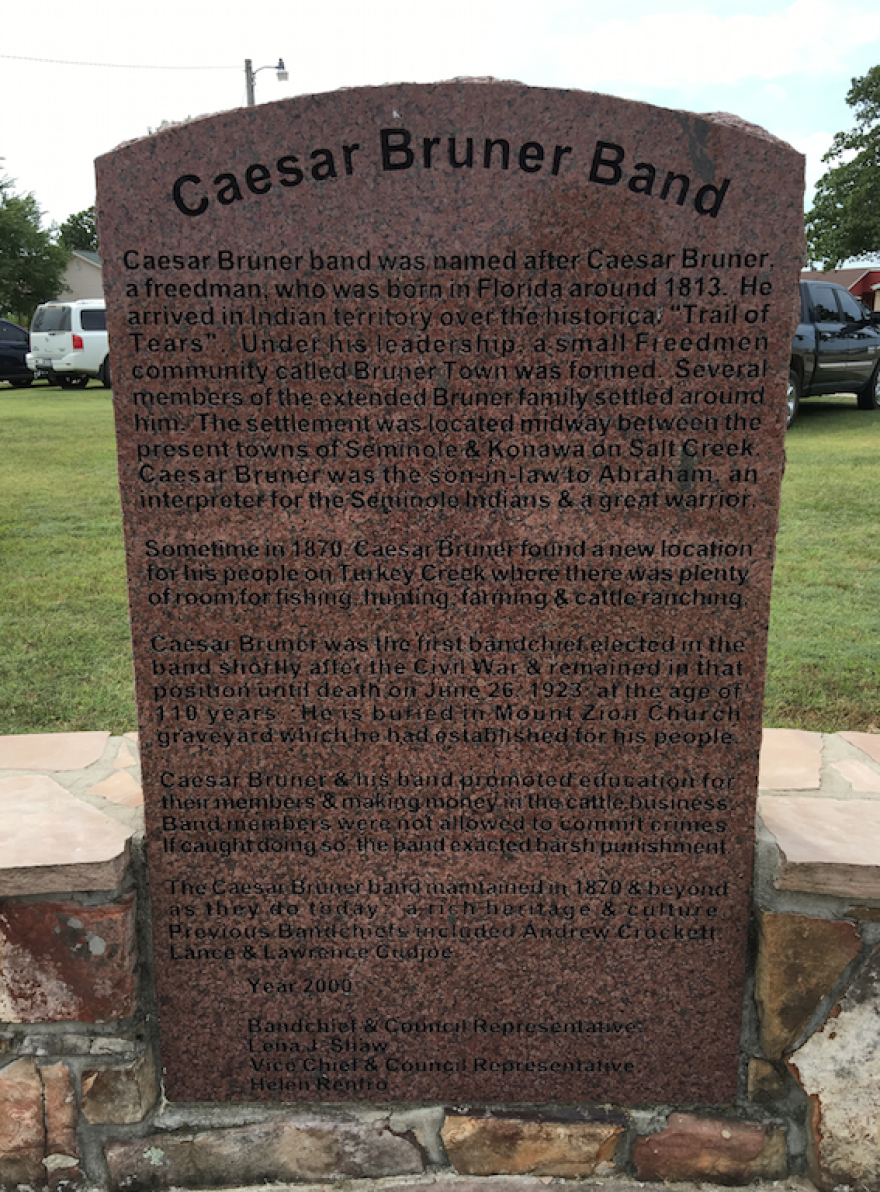

Velie argued that Seminole Freedmen were citizens based on the 1866 treaty. But records show their association with the tribe dates back long before that. In the 1700’s, when the Seminole nation was based in Florida, historical documents show that runaway slaves became part of the tribe, and that Africans fought alongside the Indians during the Seminole wars in the early 1800’s. But this long history still doesn’t equal native bloodlines according to tribal members like Robert McCulley.

“The position of the tribes is that if we’re going to be given words and associations with things like sovereignty, and things of that nature, well then it’s absolutely that tribe’s business as far as who they allow as membership,” said McCulley.

At a recent tribal council meeting at the Mekusukey Mission in Seminole, McCulley, the tribe’s director of transportation, fanned his face to cool off in the Oklahoma humidity while he waited outside for his turn to speak to the council. He says he and other tribal officials have nothing against the Freedmen. He says it’s a matter of sovereignty.

“I would hesitate at all to call it a race issue. It’s a matter of principle and a matter of practice as far as who we are as a people and how we govern ourselves.”

He’s not questioning the freedman’s citizenship - as it’s laid out in the treaty. But, he says, full benefits of tribal membership should only go to those who can prove their bloodline.

Here’s where it gets even more complicated. Tribes receive federal funding for things like housing and health care based on their membership. And, they count the freedmen among their ranks when they give those numbers. Freedman LeEtta Osborne Sampson says if they’re counted, they should be entitled to those benefits.

“The principle is our heritage. This is a part of our heritage. This is not a handout. This is not someone asking for charity. This is a people that belong here. This is how I was raised and been in this nation.

By denying the freedman access to some tribal benefits, they are technically in violation of federal law. But what this really comes down to is two historically disadvantaged populations each fighting for what they think is right. On the one hand, sovereignty for Native American tribes.

On the other hand, restitution for many years of slavery and fulfilling a promise made so many years ago. Neither group is backing down.